The Terracotta Army Legacy of the First Emperor of China Review

The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army, The High Museum of Fine art, Atlanta, 16 November 2008–nineteen April 2009, curated by Jane Portal.

The Showtime Emperor: China's Terra cotta Army, edited by Jane Portal, with the assistance of Hiromi Kinoshita. Pp. 240, figs. 201, map ane. Loftier Museum of Art, Atlanta 2008. $45 (cloth); $35 (paper). ISBN 978-1932543254 (cloth); 978-1932543261 (paper).

The Outset Emperor: Communist china'south Terracotta Ground forces focuses on Emperor Qin Shihuang and the grand empire he created during his rule from 221 to 210 B.C.Eastward. The exhibition at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, originally shown in a larger version at the British Museum in 2007/2008, displays about 100 objects, primarily from the Qin dynasty (221–206 B.C.E.), and examines them within their historical and archaeological contexts to reassess the legacy of China's Commencement Emperor and investigate the life and thought of his time.1 About half of the loans are from the Museum of the Terracotta Warriors2 in Lintong County, Shaanxi Province, which was congenital at the site of the First Emperor's tomb in 1979. The remaining loans are from ix other museums in Shaanxi Province and the British Museum. This is not the first fourth dimension that terracotta warriors have been shown in the United States;iii however, the electric current exhibition is the first one completely devoted to the Get-go Emperor and the Qin dynasty. The exhibition is accompanied by a handsomely produced catalogue with contributions by leading western scholars and prominent Chinese curators who have been involved with these works since their discovery.4

Before the 1970s, our cognition of the Qin dynasty was mostly derived from historical texts, many of which are incomplete, biased, or fifty-fifty contradistinct. The spectacular works of the Qin dynasty, recovered past means of archaeological excavations during the last 35 years at Lintong, a county almost 40 km due east of Eleven'an in Shaanxi Province, establish a reliable new source that fundamentally transforms our agreement of this critical phase of early People's republic of china.

The Legacy of the First Emperor

The exhibition's installation, which progresses from the legacy of the First Emperor's life to the ane associated with his death, is divided into four galleries, each organized around a different overarching theme. The outset gallery introduces his lifetime achievements. Its display is bundled in a generous infinite that allows the use of freestanding cases. Here, weapons (including a reconstructed crossbow and arrows and a bronze sword) and signal bells imply the military prowess of the Qin,v while items such as ritual vessels and money manifest the political and cultural achievements of Qin in the history of China.half-dozen An imposing wall panel reproduces an enlarged rubbing from a 10th-century stone stele of an archaic Qin inscription that commemorates one of the v historic inspection tours the emperor made after he had unified the country, emulating the legendary sage kings who ruled the universe.7 This reliable 10th-century re-create of the lost original records the emperor'southward accomplishment of "eliminating the six brutal powers" and "unifying [all that is] nether sky."

Qin, named after the feoff it received from a king of the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 B.C.Due east.), had rather apprehensive beginnings. When it offset appeared in Red china's political arena in the ninth century B.C.Eastward., Qin was a minor country in the distant west, far away from the traditional heartland, where China's start political country, the Shang dynasty, arose in the mid second millennium B.C.E. Qin gradually expanded its territories, moving its capital letter eastward, as it continuously fended off attacks from nomadic neighbors in the north and west. In the late 5th century B.C.E., Qin began to adopt radical changes in its legal, political, military, and social institutions that transformed it into a dominant forcefulness among the rivaling states. By introducing a organisation of ranks achieved past merit and advanced military technology, Qin built an effective army with which its last male monarch, who became the First Emperor, eliminated all adversaries and established the Qin dynasty.

The new central government of Qin introduced a standard set up of weights and measures to replace the different series of units used by the separate states. Qin bandage in bronze and distributed a large quantity of its own standard units, which are exemplified by the heavy bronze weight in the first gallery (fig. one).eight Its inscription records ii edicts issued respectively by the First and Second Emperors to enforce use of the standard equally well as to certificate the statuary'south own weight, its engagement and place of industry, and the officials and workers involved in its production. A nearby example contains different currencies in diverse shapes used by the states earlier their conquest and likewise features the minor-looking Qin money, a small circular disk with a foursquare pigsty, which became the normal course of money for all successive dynasties until the outset of the 20th century.9 The standardization of coinage resulted in economic convenience and enabled the effective running of a centralized authorities. The implementation of a standard script was an even more important innovation. The Chinese writing system, invented before 1200 B.C.E., had become particularly circuitous by the beginning of the Qin dynasty. Variations and inconsistencies among scripts posed an obstacle to communication among the agencies of the new government. The Qin-reformed standard script, which paved the manner for the further development of Chinese writing, contributed significantly to political and cultural unification.10 In fact, the nigh lasting legacy of Qin was the establishment of a unified land with a centralized authorities as a cultural ideal. People's republic of china has largely remained united for the roughly ii,000 years since Qin, though it has occasionally suffered periods of sectionalisation caused by internal or external forces.

Qin Architecture

Unfortunately, all the architectural grandeur of the Qin is gone. Qin buildings, constructed with perishable wood and earth, accept not survived aboveground. Although poets and artists had fantasized for some two,000 years about the splendid palaces at Xianyang, the Qin capital, their visions were derived from a scattering of historical sources. According to the biography of the Offset Emperor by Sima Qian, the official historian of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.Due east.), the Kickoff Emperor built hundreds of temples and palaces in and about Xianyang.11 Each time he conquered a state, he would order the construction of a new palace in the class of the one from the defeated state.12 The layout of his palaces in alignment with the constellations of the Royal Chamber and Heavenly Apex, where the King of Heaven was thought to reside, symbolized that Qin ruled both heaven and world. His most magnificent architectural caricature was the Epang Palace, built in a hunting park at the foot of Mount Li, due south of the capital. This massive circuitous consisted of numerous palaces connected by covered walks, 1 of which extended over the Wei River equally a link to the palaces in Xianyang.13 Thanks to modern archaeological excavations, nosotros are finally able to gain a sense of the shape and scale of Xianyang and its palatial buildings. The exhibition's second gallery focuses on the spectacular now-lost Qin architecture, which it evokes for visitors by augmenting excavated architectural fragments with a mod architectural model of a palace at the Qin capital, a wall panel reproducing an early 18th-century royal court painting of the Epang Palace, and a big photograph mural of another depicting a fantasy country that the emperor dreamed of visiting.

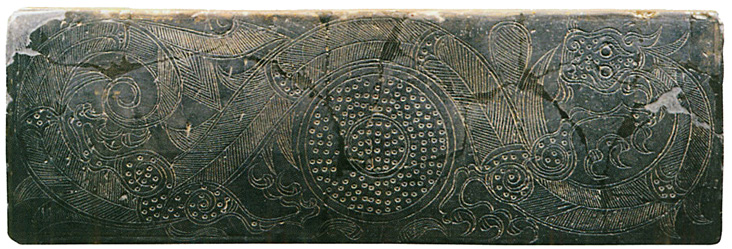

The site of ancient Xianyang (ca. xv km east of mod Xianyang City) is on an elevated evidently at the pes of Jiuzong Mountain. Xianyang was established as the majuscule in 350 B.C.Due east., when the Qin purple house moved farther to the east. By the time the First Emperor unified the country, Xianyang had already grown into a sizable city.fourteen During approximately the terminal one-half-century, archaeologists accept found 33 major architectural remains, plus pottery workshops, statuary and iron foundries, brick and tile factories, and armories in an area roughly fifty km2.15 The largest architectural complex, which measures nigh 900 x 570 chiliad and comprises viii major buildings, is believed to be the Xianyang Palace of the First Emperor. The main building, originally 117 x 45 k, was in a squat U shape composed of 2 identical multistoried wings with many halls joined by stairways, corridors, and open balconies. The floors of the rooms were either constructed with harbinger-tempered dirt or paved with square clay bricks, some of which had pressed surface patterns. The steps of the corridors were built with large hollow bricks embellished with geometric designs and fantastic beasts. Two superb examples, each measuring near 118 x 39 cm, are on display.16 1 of these is engraved in fluent lines with a spirited dragon, whose sinuous trunk writhes around a large ritual jade disk (fig. ii). There are also pottery rooftile ends,17 some of which conduct the palaces' names, while others take molded floral or fauna designs. The exquisite modern wooden model of the west wing of Xianyang Palace, showing its three stories and two-tiered roofs, is based on archaeological finds besides as on representations of architecture from Qin wall paintings and engraved stones.18

The Terracotta Army

The third gallery, devoted to striking archaeological finds from the Showtime Emperor's tomb at Lintong, Shaanxi, is the highlight of the exhibition. 8 life-sized terracotta sculptures of warriors and modern replicas of two half-life-sized bronze sculptures of equus caballus-drawn chariots are installed at the center of the room (fig. 3). The sculptures are placed on long platforms that enable visitors to view them from every angle. This gallery'south walls are painted black and punctuated at the archway and leave by enlarged ancient Chinese texts in red print. The combination of these two bold colors, perhaps inspired by the fine art of Qin lacquer,nineteen bestows the display space with an monumental solemnity, while a large photo mural of a burial pit at the far terminate of the gallery gives the impression of the terracotta regular army continuing its march in endless rows.

Although the terracotta warriors are at present world famous, few people know that their initial discovery was completely accidental. In the spring of 1974, a group of farmers digging for h2o in a field near their village in Lintong County—about 1.v km from the tomb of the First Emperor—came upon fragments of life-sized terracotta figures.twenty A team of archaeologists was dispatched from the Shaanxi Provincial Archaeological Institute to investigate the discovery. Controlled excavations shortly uncovered a large burial pit about 230 g long by 62 one thousand wide and 4.v to 6.5 g deep, in which about vi,000 life-sized terracotta figures of soldiers and horses plus remains of wooden chariots were detected. During the following ii years, archaeologists found two more than burial pits. The total surface area of the three pits is more than 200,000 g2, and the total number of terracotta sculptures belonging to the pits is close to eight,000.21

The burying pits themselves are sophisticated constructions. Their basis and wall surfaces have been reinforced with thick layers of rammed earth every bit hard as concrete. X embankments, also built with rammed globe, run lengthwise through each of the three pits, dividing the space of each into xi corridors. The corridors' floors are paved with bricks and their walls lined with wooden beams and posts. On the basis of fragments on the pits' floors, archaeologists believe that the embankments and posts of each pit once held a huge ceiling of wooden beams topped by reed mats that were covered with layers of world.22

The approximately 6,000 terracotta figures in pit 1, the largest of the three pits, are believed to represent the central Qin army, comprised of human foot soldiers, armored officers, and four-horse chariots, in formation as if on the battlefield.23 Pit 2, an L-shaped earth construction of 6,000 10002 to the northeast of pit ane, houses a cavalry consisting of 108 armored riders standing in front of their horses, a battalion of 64 four-equus caballus chariots, each containing 3 charioteers, a battalion of 300 archers and foot soldiers, and a large combined unit of measurement of most 300 charioteers, cavalry, and foot soldiers. Pit 3, the smallest one, is believed to stand for the ground forces'south headquarters; it contains one chariot at the eye plus 68 officers and human foot soldiers continuing at attention with their backs toward the pit's walls.

To date, more than 1,900 sculptures have been recovered, and thus well-nigh of the approximately viii,000 sculptures nonetheless remain untouched underground in the three pits. The excavated sculptures of soldiers fall into three major categories: infantry, cavalry, and charioteers. The infantry can be further divided into subcategories, including officers of high, middle, and low rank, light-armed and heavily armored pes soldiers, and continuing and kneeling archers. The eight warriors on display have been carefully selected from pits one and 2 so that each one represents a unlike type (see fig. 3). They have been arranged in rows to evoke the original arrangement of terra cotta warriors in the pits. An armored infantryman, wearing a articulatio genus-high tunic and body armor, and a light infantryman, wearing a tunic without armor, stand in the outset row.24 Behind them are a senior officer and a standing archer.25 The officer, with three ribbons on his chest signifying his rank, wears long, beribboned armor and a alpine, double-tailed headdress. The men in the third row are too officers: an unarmored senior officer with a tall, double-tailed headdress and a low-ranking charioteer officer in an armored tunic.26 The concluding row contains a chariot driver and a cavalryman with his equus caballus.27 While the driver is equipped with long armor for maximum protection, the cavalryman wears short, calorie-free armor, providing mobility for riding and shooting arrows. Each of the eight soldiers has a unlike face and body type, and their hairdos, mustaches, and/or beards besides vary from ane another.

The thousands of individualized terra cotta sculptures resulted from a mass-production procedure. Arms, easily, and heads were fabricated in molds equally separate modules, which were and so joined with the anxiety and torso. In the concluding steps before firing, dirt was practical to the surface of the sculptures so that artists could model the faces and hairdos individually. Other body parts, costumes, and armor were besides reworked individually. The finished warrior sculptures were thus made to look as diverse equally a existent army equanimous of human being beings. A mod miniature model of a Qin sculpture workshop, displayed in the warriors' gallery, vividly illustrates the process of their manufacture.28 Archaeologists have all the same to locate the kilns where the terracotta sculptures were fired, only the more than 80 workshop and craftsmen's names stamped or engraved on the sculptures propose that a big number of workshops must take been involved.29

Today the sculptures are either grayness or reddish—the colors of the terracotta itself; however, they were originally painted in bright colors. The warriors' faces were stake yellow or pink flesh colors, and their robes and trousers red, green, blueish, royal, or black. The borders of the armor on senior officers bore colorful, intricate geometric patterns, which faithfully copied gimmicky textiles. Chemical assay has revealed the painting process, which employed many mineral colors, including cinnabar, azurite, and malachite,thirty practical on tiptop of a layer of lacquer.31 The several conserved examples of sculpture with preserved pigments are too delicate to travel. But a detailed color illustration helps the exhibition visitor visualize the warriors' original colorful appearance.

The two modernistic replicas of half-life-sized statuary chariots in the third gallery are nearly as striking every bit the terracotta warriors (run across fig. three). The originals were found in 1980, in a wooden bedroom alongside a burial pit at the w end of the emperor'southward tomb mound.32 When plant, each chariot was cleaved into more than i,000 pieces. Conservators worked for two years to restore them to their original splendor, only the chariots are too delicate to travel, and, hence, painstakingly produced replicas are displayed in the exhibition. The bronze chariots were naturalistically painted, and these replicas even evidence the remaining pigments.

The first one depicts a light chariot, too known as the alpine chariot, which is drawn past iv smartly trimmed and elaborately caparisoned horses.33 The commuter rides in a standing posture nether a large, circular umbrellalike awning. The 2d four-horse chariot has a rectangular machine with movable windows and covered by an oval canopy.34 The driver sits in front earlier this chariot's large and deep car, in which passengers may either sit or sleep. This second vehicle was peradventure the kind of carriage in which the First Emperor rode when he toured the country. Qin craftsmen significantly improved the design of the chariot, which had been introduced from western asia in the 2d millennium B.C.East.35

The Future of Archæology at the Commencement Emperor's Tomb

In the exhibition's fourth and last gallery, a new chapter begins about the investigation of the First Emperor's tomb, or, in other words, his thou underground empire. Equally the wall panels land, this final section is devoted to "Recent Discoveries" and "The Futurity of the Tomb."36 The ten recent finds displayed hither are at to the lowest degree as fascinating as the terra cotta warriors.

The limestone armor on display is one of 87 suits that were unearthed from a storage pit during a trial excavation in 1999.37 This restored suit of armor consists of 612 limestone plates laced together by flat copper strips. Information technology is 74 cm long, 128 cm effectually the waist, and weighs xviii kg. The stone armor, which is besides heavy to have been worn, must have been intended for protection against evil spirits in the afterlife. Scholars believe that the stone armor represents bodily contemporaneous armor fabricated either entirely of leather or of a combination of leather and iron, like the examples recovered past archaeology.38

The bronze h2o birds on brandish, a swimming swan and a standing crane with a fish in its beak (fig. four), are ii of the 46 life-sized bronze birds—twenty swans, xx geese, and half dozen cranes—that were constitute in 2000 inside an surreptitious structure in the shape of a riverbank inside a burial pit (K0007).39 The birds are rendered with such remarkably realistic details that specialists have been able to identify their species. And they, as well, were originally naturalistically painted.

11 life-sized terracotta sculptures of sitting or kneeling musicians were found in a tunnel in the same pit. The positions of their hands suggest that they once held musical instruments that have not survived. The musicians wear similar costumes, but their faces are highly individualized. 2 are on display.40 According to Duan Qingbo ("Entertainment for the Afterlife" [201]), the pit containing the musicians and birds (K0007) probably represented an office of the Qin court that "provided tame birds for musical performances for the emperor."

The well-nigh impressive of the more contempo finds is the terracotta sculpture of a strongman, possibly a weight lifter (fig. 5), which was found with ten other life-sized figures in a burying pit (K9901) virtually the emperor'south tomb in 1999.41 These standing human figures wear just short skirts, so that their realistically modeled torsos are bare. The wrestler, with brawny muscles and a protruding stomach, is the most remarkable of all.

The awe-inspiring terra cotta sculptures—particularly examples that, like the strongman, brandish astonishingly realistic anatomical features—pique the intellectual curiosity of art historians. The engineering science for making such figures was readily available to the Chinese, who had already been producing circuitous, precise ceramic molds to cast statuary for more than 1,000 years. Just lifelike, life-sized sculptures of human beings were unknown in early on Chinese cultures.

Where did the inspiration for such sculptures come from? Although suggestions about cultural diffusion currently tend to be scorned and are often dismissed, these faithfully represented Chinese human figures nonetheless persistently remind us of the art of ancient Persia and the Hellenistic earth. Show from archaeology suggests that early in the 9th century B.C.E., the Qin country already had contact with the West.42 Their nomadic neighbors on the steppes were an agile conduit for China's exchange with Central and western Asia and ultimately with Europe.43 As we have seen, nomads were responsible for the introduction of chariots and, most probably, too for the earliest import of a variety of jade (nephrite) from the Tarim Basin. Recently, archaeologists have found drinking glass beads in a late fourth-century B.C.E. Qin tomb, which they accept identified as a western import.44 Fifty-fifty more surprising is the presence at the same site of a blue-glazed (perhaps faience) beaker, which is unmistakably of ancient Mediterranean origin.45 More evidence will exist needed to resolve complex issues of cross-cultural influence. However, given the vigorous step of fieldwork and rapid advances in research, the outlook for major future discoveries in Chinese archaeology looks bright.

As spectacular as they are, the works on display represent merely a small fraction of the numerous discoveries archaeologists have made over the last 35 years in the vicinity of the First Emperor'due south tomb. All-encompassing excavations and surveys accept revealed the tomb itself to be a massive complex that includes a cardinal mound, which is a human being-fabricated hill 45 thousand high, surrounded by a large memorial hall, imperial kitchens for the preparation of sacrificial food, and numerous burial pits filled with a variety of offerings.46 The walled tomb circuitous occupies a rectangular site with a area of 2.135 km2. The tomb chamber, or so-called cloak-and-dagger palace, lies beneath the earthen mound. Preliminary investigations have establish the chamber'south walls to be 460 m long and 392 thou broad; its depth is speculated to exist between 20 and 30 m. Tests of earth under the mound indicate that it contains an extraordinarily high level of mercury (Duan Qingbo, "Scientific Studies of the High Level of Mercury in Qin Shihuangdi's Tomb" [204]). This appears to corroborate the description of the tomb past Sima Qian: "Mercury was used to fashion the hundreds of rivers, the Yellowish River and the Yangtze, and the seas in such a way that they flowed."47

Conclusion

This exhibition is a remarkable presentation of ane of the most of import archaeological discoveries made in People's republic of china during the last half-century. The extraordinary works on display—tangible evidence of the beingness, achievements, and vision of the First Emperor—tell his story more vividly than written sources. Anyone interested in history, archaeology, art, or compages should see this testify. The visitor will come away with an eye-opening, up-to-date knowledge and understanding of early on China and thus of the formation of possibly the greatest civilisation in the globe.

Section of Asian Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

thou 5th Artery

New York, New York 10028

jason.dominicus@metmuseum.org

* The author would like to give thanks Museum Review Editor Beth Cohen for her aid with the revision of this review and Cassandra Streich, senior director of public relations at the High Museum of Art, for her assistance with the illustrations.

Works Cited

Boardman, J. 1994. The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. London: Thames & Hudson.

Bunker, Eastward.C. 2002. Nomadic Art of the Eastern Eurasian Steppes: The Eugene Five. Thaw and Other New York Collections. Exhibition catalogue. New York and New Haven: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art and Yale University Printing.

Gansu Provincial Plant of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Museum of Zhangjiachuan Hui Autonomous County. 2008. "2006 Excavation on the Majiayuan Cemetery of the Warring States Menstruation in Zhangjiachuan Autonomous County of Hui Nationality, Gansu" (in Chinese). Wenwu ix:4–28.

Han Wei. 1996. "Some Remarks on the Gilded Leaves of the Qin Dynasty from Lixian, Gansu" (in Chinese). Wenwu 6:4–eleven.

Loewe, M., and Eastward. Shaughnessy, eds. 1999. The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Printing.

Museum of the Terra cotta Warriors and Horses of Emperor Qin Shihuang and Shaanxi Provincial Archaeological Constitute. 1998. The Bronze Chariots and Horses Unearthed from the Qin Shihuang Mausoleum—An Digging Written report (in Chinese). Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House.

Portal, J., ed. 2007. The Offset Emperor: Communist china's Terracotta Army. London: The British Museum Press.

Shaanxi Provincial Archaeological Plant. 2004. Archaeological Written report on the Investigations and Excavations at the Qin Uppercase Xianyang (in Chinese). Beijing: Science Press.

Shaanxi Provincial Archaeological Found and Museum of the Terracotta Warriors and Horses of Emperor Qin Shihuang. 2000. Excavation of the Precinct of Qin Shihuang's Mausoleum in 1999 (in Chinese). Beijing: Scientific discipline Press.

Shaanxi Provincial Archaeological Constitute and Museum of the Terra cotta Warriors and Horses of Emperor Qin Shihuang. 2007. Report on Archaeological Researches of the Qin Shihuang Mausoleum Precinct, 2001–2003 (in Chinese). Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing Firm.

Shiji. Past Sima Qian. Zhonghua shuju edition.

Tao Fu. 2004. "Preliminary Studies on the Reconstruction of Qin Xianyang Palace at Site one" (in Chinese). In Archaeological Written report on the Investigations and Excavations at the Qin Capital Xianyang, 763–75. Beijing: Science Press.

Thieme, C., and Due east. Emmerling. 2001. "On the Polychromy of the Terracotta Regular army." In Qin Shihuang: Dice Terrakottaarmee des ersten chinesischen Kaisers/Qin Shihuang: The Terra cotta Army of the Get-go Chinese Emperor/秦始皇陵兵馬俑, edited by C. Blänsdorf, Due east. Emmerling, and M. Petzet, 334–69. Arbeitshefte des Bayerischen Landesamtes für Denkmalpflege 83. Munich: Bayerishes Landesamt für Denkmalpflege.

Twitchett, D., and Grand. Loewe, eds. 1986. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 1, The Ch'in and Han Empires 221 B.C.–A.D. 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yuan Zhongyi. 1990. A Report of Terracotta Warriors and Horses of Qin Shihuang Mausoleum (in Chinese). Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House.

Yuan Zhongyi. 2002. 秦始皇陵考古發現與研究. [The Discovery and Study of the Tomb of the First Emperor of Qin]. Xi'an: Shaanxi People's Printing.

rollandhamakfame89.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.ajaonline.org/online-review-museum/369